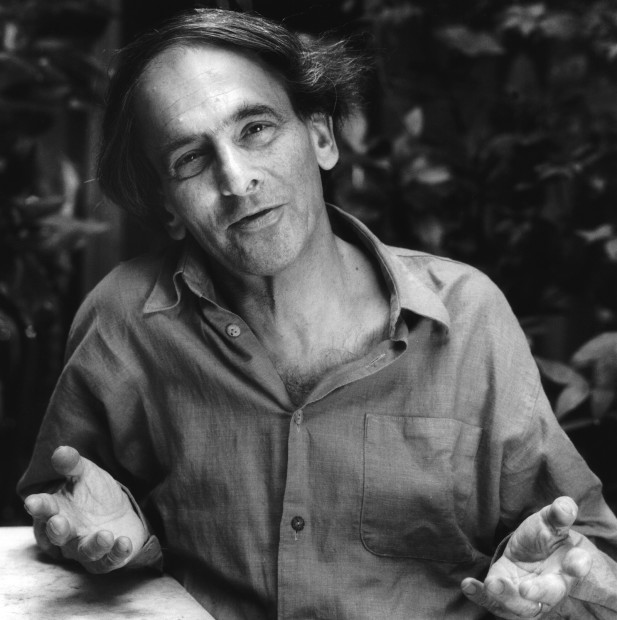

Twenty Years On: Raphael Samuel

It is twenty years since

the death of one of the most significant socialist historians of the post-1945

era, Raphael Samuel. In the age of post-truth particularly his work, focused as

it was on the recovery of working class and plebeian history and dominated by

the rigour of the carefully researched footnote deserves to be not just

remembered but taken as an exemplar.

Below is an obituary that

appeared in Socialist Review January 1997 by Keith Flett

Obituary: Artisan

of history

Raphael

Samuel (26 Dec 1934- 9 Dec 1996)

Keith Flett

Raphael

Samuel, who has died aged 61, was a youthful member of the Communist Party

Historians’ Group in the 1950s when its leading members included Eric Hobsbawm

and E. P. Thompson. However, he left the CP in 1956 and as a socialist

historian he was very much a child of the `new left’ and the upheavals of the

1960s.

Samuel studied under Christopher Hill at Balliol College,

Oxford, in the

early 1950s, but, unlike the older generation of Marxist historians, Samuel

never sought academic advancement. His published work, usually under the banner

of the History Workshop, was invariably a collaborative exercise, and for more

than 30 years from 1962 he remained a tutor at Ruskin

College, Oxford, encouraging mature trade union

students to take an interest in historical research.

History Workshop collections edited by Samuel, such as Village Life and Labour and Miners, Quarrymen and Saltworkers, opened up a focus on the

history of ordinary working people, and the essays were usually written by

`worker historians’ often students of Samuel at Ruskin.

So thirteen History Workshop pamphlets including Stan

Shipley’s Club Life and Socialism in

mid-Victorian London

were published between 1970 and 1974. Shipley had been an AEU branch secretary in Walthamstow.

Perhaps ironically, shortly before his death Samuel was

persuaded to take a long overdue and much deserved professorship at a new

centre for the study of community in the East End of London at the University of East London.

Samuel was a key figure behind the rise of the History

Workshop movement which began life at Ruskin

College, Oxford,

in 1966 as an informal seminar on the English countryside in the 19th century.

The principal, Samuel has related, almost closed it down, worried that students

were listening to each other rather than to the lecturers. History Workshop

Journal followed in 1975.

The Workshops in particular brought together large numbers

of rank and file socialist historians committed to recovering the past from the

viewpoint of ordinary people. Early sessions famously included topics such as

`A Day With the Chartists’ which sought to recreate the ideas, experiences and

conditions that the Chartists had encountered.

The Workshop in particular became very much a product, as

Samuel recorded in People’s History and Socialist Theory [1981], of the events

and enthusiasms of 1968. Ruskin was out on strike days before the Paris events of May 1968.

Raphael Samuel was one of the most prominent historians in

the country to support history from below the attempt to actively recover the

history of ordinary people and their movements. In many ways this was a step

forward from the sometimes rather rigid orthodoxies of more mechanical Marxist

histories. It fed in directly, too, to the resurgence of socialist ideas after

1968 and to the birth of the women’s movement in which the History Workshop

Conference of November 1968 played a central organising role.

Samuel could be fiercely critical of socialists with whom

he disagreed. Debate has raged, for example, about whether a series of articles

he wrote about the Communist Party in the 1940s and 1950s in New Left Review

under the title `The Lost World of British Communism’ was an attempt to write

an affectionate history from below of what it had been like to be a CP member

before 1956 or an attack on any kind of left wing political activism.

He was nevertheless a great enthusiast for history and a

great encourager of people engaged in socialist historical research. His energy

and productivity knew no bounds, whether it was in organising meetings or

producing articles.

With his untimely death socialists can make a preliminary

attempt to draw a balance sheet of what Raphael achieved. The History Workshop

movement, of which Samuel published a 25 year history in 1991, has declined and

become, to an extent, sucked into academic respectability.

In recent years it has dropped its masthead describing it

as a journal of `socialist and feminist historians’ as it has reflected the

pessimism of some on the left about the prospects for change after the collapse

of Stalinism. Certainly the early, welcome, focus on working class history and

movements and direct links to political activity in the present have largely

gone.

Gone too is the commitment to

`worker historians’. In its place has come a certain attraction to the ideas of

postmodernism. Both the History Workshop where it still functions and History Workshop Journal, however,

remain battlegrounds, in historical terms, for many of the ideas, good and bad, which are current on the left.

Their influence, and that of Samuel, has been immense.

Groups and publications inspired by them exist in many countries.

History from below as practised by Samuel and others has

also met its limitations. In many cases it has led towards an interest in

ephemera and detailed micro-

histories which, while of interest to the historian, are

certainly not about changing the world. Samuel himself in recent years became

increasingly interested, as his 1994 collection of articles Theatres of Memory indicates, in

recovering the popular history of culture, cultural objects and artefacts.

Samuel saw this interest in heritage as a real living people’s history,

genuinely democratic and open to all. It is as a people’s historian rather than

as a socialist historian that he would probably wish to be remembered.

Even so socialist history in this country would have been

and will be much the poorer without Raphael. He kept his commitment and his

ability to argue to the end. I came across him at the Bishopsgate Institute,

opposite Liverpool Street station, which

was to be the centre of his new chair, weeks before his death.

Despite being terribly ill he found time not only to

enquire into my own research but to have a spirited debate about whether

Charles Bradlaugh’s National Secular Society, formed in 1866, was a

proto-Labour Party. That was Raphael, argumentative and passionate about his

history to the end. He was and remained a real product of the 1960s with

all the good and bad points that flow from that.

Republished in London Socialist Historians Group Newsletter 60 (Spring 2017).